DefCamp D-CTF Qualifiers 2015: Writeups

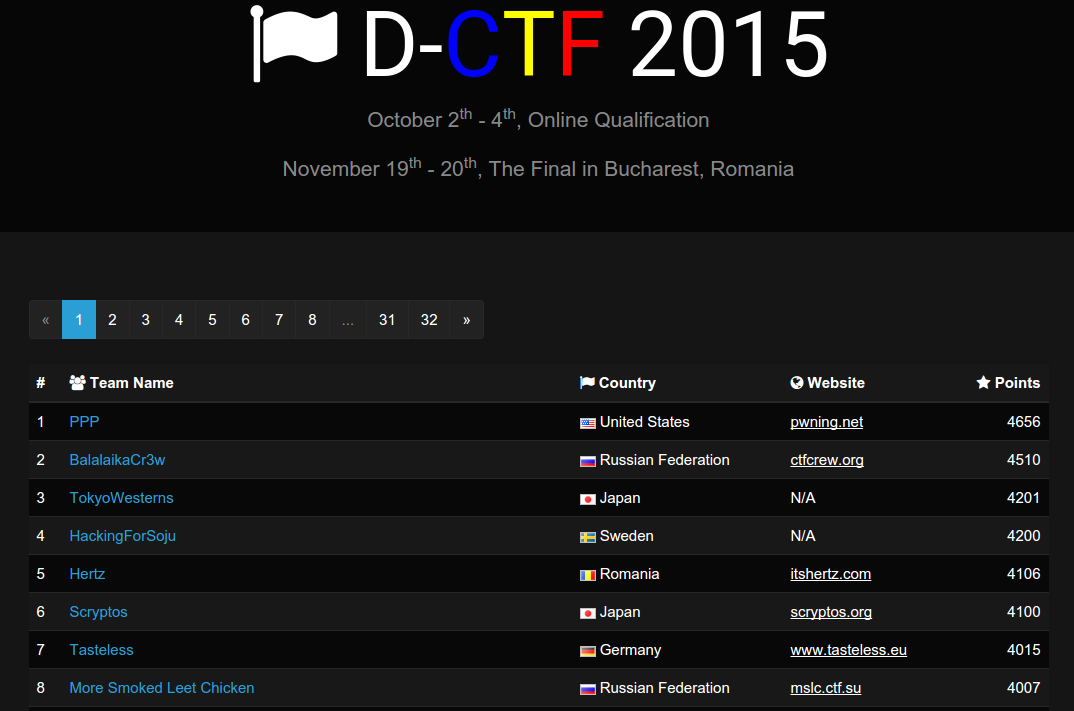

A few weeks ago we participated in the DefCamp D-CTF qualifiers. We performed really well and ended up in fourth place, just a single point behind number three. This earned us a place in the finals in Bucharest at the DefCamp conference.

This writeup will explain the challenges I solved. I try to keep the descriptions fairly brief so if you feel that you would like to know more details, please leave a comment.

- Crypto 50: 11

- Crypto 200: No Crypto

- Misc 100: She said it doesn’t matter

- Misc 200: Try Harder

- Misc 350: Emotional Roller Coaster

- Reversing 100: Entry Language

Total contribution: 1000

Crypto 50: 11

In this challenge we were given a text file with eleven chiphers which were said to all have been encrypted with the same stream cipher.

A stream cipher encrypts by generating a stream of pseudo-random data and XOR:ing it with the plaintext. We denote this as . The problem with doing this with the same stream several times is that the key is repeated. Thus if we take two ciphertexts and XOR them we get: So now we have just the plaintexts entangled with each other but the key removed. How does this help us?

One interesting thing about the ASCII encoding is that the lowercase and uppercase letters are exactly 32 steps from each other. Furthermore, a space is 32 in decimal. This means that by XOR:ing a letter with a space you flip the case but retain the same letter.

This means that if we have two plaintexts “A “ and “ B” encrypted and XOR them with each other, we get “ab”. Also, when we know the plaintext at one position we can recover the key at that position and therefore all plaintexts at that position by computing:

By XOR:ing every ciphertext with each other ciphertext, we can use the 110 combinations to extract possible letters at all positions where there is a space somewhere in one of the plaintexts. Combining this with filling in gaps in words and thus getting even more parts of the key, we finally extract the eleventh plaintext which is the flag.

Flag: “when using a stream cipher, never use the key more than once!”

Crypto 200: No Crypto

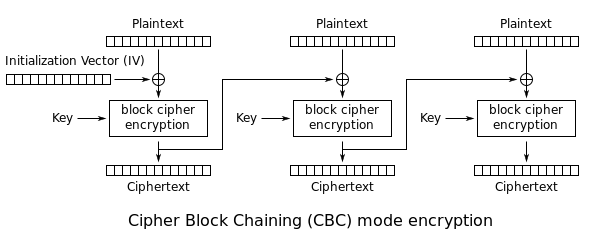

The challenge consisted of two plaintexts, and a ciphertext which was the first plaintext encrypted with AES-CBC with an unknown key. The question was “how would you change the ciphertext so that when decrypted it would instead give the second plaintext?”.””

The first plaintext was “Pass: sup3r31337. Don’t loose it!” The second plaintext was “Pass: notAs3cre7. Don’t loose it!” The cipher we were given was “4f3a0e1791e8c8e5fefe93f50df4d8061fee884bcc5ea90503b6ac1422bda2b2b7e6a975bfc555f44f7dbcc30aa1fd5e” with an IV of “19a9d10c3b155b55982a54439cb05dce”.

The text we are looking to change is only in the first block which makes this easy to solve. Looking at how CBC works, we know that the first block of the ciphertext consists of:

This means that when decrypting, we get the message by doing

were E and D is AES encryption and decryption respectively. This means that by manipulating the IV, we can affect the result of the encryption. If we take the IV to be

then the decryption becomes

Thus we have transformed the decrypted plaintext from the first to the second. Therefore the flag is the new IV.

Flag: “19a9d10c3b15464f9c585543cef10bce”

Misc. 100: She said it doesn’t matter

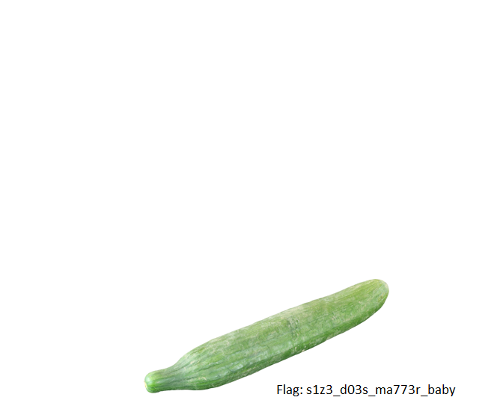

In this challenge we were given a very strange looking PNG file.

Some viewer refused to view it altogether while some show a wierd blob of color and a diagonal line. Looking at the file with the windows tool “PNG Analyzer”, we see that the actual data block size does not match the stated size in the PNG header. Additionally, the CRC checksums are not correct. Changing the size in the header to actually match the data size and then fixing the CRC checksums gives us the original image back.

Flag: “s1z3_d03s_ma773r_baby”

Misc. 200: Try Harder

This was a multi-part challenge in which we first were given to compressed files, “misc200.part0.jpg.gz” and “part3.zip”. The second one was password protected. Trusting the names, I started with looking at the first one. Extracting it gave us a roughly 4Gb large file which according to “file” is not a jpeg as the names suggests but instead a “DOS/MBR boot sector”. We could mount it and explore the contents manually but I chose to run “binwalk” in extraction mode to get all known file types inside it.

This gives us a file called “part1.zip”. This archive contains a file called “3pm.redrah-yrt” which is “try-harder.mp3” spelled backwards. Looking at the metadata with “exiftool” we find that there is a comment “aHR0cDovL2RjdGYuZGVmLmNhbXAvX19kbmxkX18yMDE1X18vcGFydDEuaHRtbA” which looks a lot like base 64 encoded data. Adding the missing “==” padding at the end and running it through “base64 -d” gives an URL: “http://dctf.def.camp/__dnld__2015__/part1.html”. This URL contains the description of what a CTF is also found on ctftime.org, however, some of the spaces have been replaced by a tab. Collecting them together and taking the spaces as zeroes and the tabs as ones gives you a binary string.

0101001101100101011000110110111101101110011001000010000001110000 0110000101110010011101000010000001101001011011100010000001101101 0110100101110011011000110011001000110000001100000111000001100001 01110010011101000011001000101110011110100110100101110000

Decoding this string as ASCII gives a new hint “Second part in misc200part2.zip”. This file can then be downloaded from “http://dctf.def.camp/__dnld__2015__/misc200part2.zip”. This archive contains two files “file1.bmp” and “file2”. The first one is a BMP which some random lines and shapes in it and the other is a file with some random bytes. Both the files are of equal length and the second one starts with a series of null bytes. This means that XOR:ing the two files together would keep the BMP header untouched.

with open('file1.bmp', 'rb') as file:

data1=file.read()

with open('file2', 'rb') as file:

data2=file.read()

with open('file3.bmp', 'wb') as file:

file.write(bytes(map(lambda x: x[0]^x[1], zip(data1, data2))))Doing this gives us a new BMP file which contains the password for the last part, “binary_and_xor_is_how_we_all_start”. Using this as a password for part3.zip gives us an image of the DCTF organizers and a hand written note which, after some difficulties with the handwriting turns out to be the flag.

Flag: DCTF{711389441a47c19a244c8473ee5aceff}

Misc. 350: Emotional Roller Coaster

This was a really interesting level with a nice twist. The challenge had a description including “you are the target”. By listening on the network traffic with Wireshark while being connected to the VPN, you could see an incoming DNS request. Specifically the request was an MX request for the host name of your client on the VPN. Setting up a DNS server and answering to this request with for example your IP address you could see another incoming connection on the SMTP port. Since I didn’t have an SMTP server readily available, I proceeded to configure one locally to recieve the e-mail.

The e-mail contained an attachment in the form of a PCAP file. The PCAP was a recorded SMB file transfer of a zip archive, “emoticons.zip”. That archive contained 97 gif files of emoticons. Looking at these images with “exiftool” revealed that they all had a “Camera Model Name” metadata field with something looking like base 64 data.

They were all of equal length except for the eleventh image, indicating the the data was not in order when taking the files ordered by name. Instead, ordering the images by file modification date and concatenating the base 64 data gave us something that could be decoded to a zip file. This zip file contained a lot of junk to increase the size of the archive but also a file called “sol/flag” with the flag inside.

Flag: DCTF{e4045481e906132b24c173c5ee52cd1e}

Reversing 100: Entry Language

This was a standard “key verifier challenge”. The binary took an input and verified it to a target value. By disassembling the binary it was possible to extract the verifier code and translate it to this equivalent Python code

target = ["Dufhbmf", "pG`imos", "ewUglpt"]

for i in range(12):

if ord(target[i % 3][2 * (i/3)]) - ord(pw[i]) != 1:

print("Fail!")It is easy to see that this algorithm can be reversed and the answer extracted without any need for brute-forcing. A little algebra gives you the following Python code:

target = ["Dufhbmf", "pG`imos", "ewUglpt"]

pw = []

for i in range(12):

pw.append(chr(ord(target[i % 3][2 * (i/3)]) - 1)),

print(''.join(pw))Which prints out the flag.

Flag: “Code_Talkers”